The Lancet Respiratory Medicine doesn’t challenge the faulty reasoning behind the move to marginalise or isolate this vaccine company because of the minority shareholding by Philip Morris International (PMI), a tobacco company.

It takes the claims of activists and bureaucrats at face value without any critical appraisal.

Instead, it transcribes the celebratory statements of misguided activists and officials:

Adriana Blanco Marquizo, head of WHO FCTC, Geneva, Switzerland, told the Lancet Respiratory Medicine “This is definitely a welcome decision. The tobacco industry should not be involved in partnerships that lend credibility to the industry or could give them access to public health policy making.” However, when asked how the Canadian Government had allowed things to progress this far, she added, “It is not the role of the Secretariat of the WHO FCTC to comment on the activities or intentions of parties to the convention.”

1. Tobacco control activists make a strategic blunder

PMI has set ambitious goals to deal with the main problem associated with its business, namely the toll of death and disease caused by smoking, primarily cigarettes. It has two broad approaches to doing that:

- To migrate its consumer nicotine business from combustible tobacco to low-risk non-combustible nicotine products, such as nicotine pouches, vaping products, and smokeless or heated tobacco products.

- To diversify its operations into non-nicotine wellbeing and healthcare businesses where the company has possible advantages and synergies (in the case of vaccines, plant biotechnology, clinical trials, etc.).

This reasoning is not hard to find: it is set out in PMI’s Statement of Purpose [1]

Changes to our strategy and vision prompted the revision of our Statement of Purpose, expanding it to no longer have as its last horizon to achieve a smoke-free future, but also to encompass our strategic efforts to venture toward becoming a wellness and healthcare company. Notably, we aspire to achieve at least USD 1 billion in net revenues from such sources by 2025.

Anyone wishing to monitor its progress can easily do so. PMI net revenues from smoke-free products accounted for 32.1% of total net revenues in 2022, up from 0.2% in 2015. [2] That represents a rapid transition by any standards.

It’s unclear why so-called public health activists somehow think they are making progress by obstructing this strategy. Why do they think it is a good idea to confine a company like PMI to remain in the “merchant of death” business when it states its intention to exit?

The embarrassingly simplistic NGO view [3] of the tobacco companies is that they should just stop selling cigarettes. But any company that tried that would fail: the shareholders would sack the management, competitors would mount a hostile takeover, or the board would sell the cigarette assets as a going concern. Shareholder interests would prevail.

To get out of cigarettes, quoted companies like PMI, BAT, JTI, or Imperial need a compelling story for their shareholders. Such a story would have two main elements. First, a business plan for diversification (as above). Second, favourable changes to the external environment (taxation, regulation, communications, politics) aligned with ending the era of cigarettes.

The foolish strategists of tobacco control activism are doing the opposite. They mostly oppose migration to smoke-free nicotine products using a wide range of specious and anti-scientific arguments. They are trying to make it as difficult and unattractive as possible to diversify (see this article). Their efforts are directed at forcing tobacco companies to rely more heavily on the sales of cigarettes.

There are two further disturbing dimensions to tobacco control activism in this case.

2. An absurd approach to controlling tobacco company influence

First, the evocation of Article 5.3 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is misplaced. Tobacco control activists treat this treaty article as a kind of force majeure clause that legitimises almost anything, however ridiculous and counterproductive, that opposes a tobacco company. Yet the text of Article 5.3 is relatively innocuous: [4]

- In setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, Parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry in accordance with national law.

The article deals with inappropriate influence on tobacco-related policy-making. Can these activists explain why preventing a tobacco company from investing in a vaccine business will prevent its influence on tobacco policy? How would that influence even work? What would the vaccine company do? It is far easier for tobacco companies to invest in think tanks, lobbyists, trade associations, and interest groups or use their own resources to influence tobacco policy. For old-school tobacco industry influence, they need look no further than state-owned tobacco companies, which can influence state parties to the FCTC from the inside and even join official delegations to the FCTC meetings.

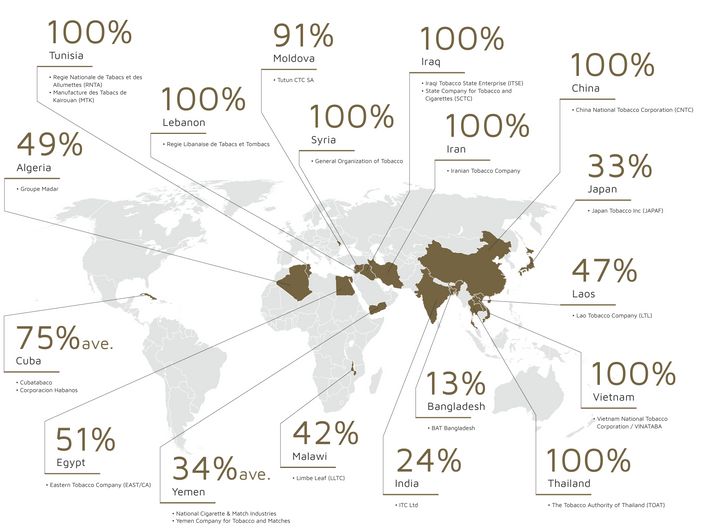

There are 18 countries where governments own 10% or more of at least one tobacco company. Of these 18 countries, 17 are signatories to the FCTC; eight countries own 100% of at least one tobacco company. [5]

Most of these state-owned tobacco companies do not have a strategy to exit from the cigarette trade. Yet, tobacco control activists focus on obstructing companies with a viable strategy for reducing their health impact. Where is the consistency, and where is the logic?

3. Appalling ethical contortions

In their efforts to obstruct companies like PMI from transformation, tobacco control activists seem entirely unconcerned with inflicting collateral damage on a vaccine company – and indeed may wish to do this deliberately. Following deliberate blockage by WHO, the promising vaccine product and company have failed. But this was not for reasons of vaccine safety or efficacy, malpractice, or excessive cost, but because of WHO’s opposition to PMI’s minority shareholding in the company making it. [6]

A year ago, officials with the agency refused to endorse a vaccine made by Quebec-based Medicago. It used a plant related to tobacco as the “factory” to produce virus-like particles that taught the immune system to fend off the virus that causes COVID-19.

Health Canada approved the vaccine Covifenz in February of last year, after studies showed two doses were 71 per cent effective in protecting adults 18 to 64 against COVID-19 infection and disease. The vaccine was 70 per cent effective against Omicron.

The Medicago technology was also widely seen as having great potential for creating both vaccines and antibody treatments for other conditions, including cancers, arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

That is a clear abuse of WHO’s mandate and ethically appalling.

Suppose Medicago had found a low-cost and easily transported COVID-19 (or other) vaccine or a vaccine more easily produced in low-income countries. What are the consequences of denying this product access to the market, as many activists wish to do on the basis of the company’s ownership? In order to attack a tobacco company while it tries to do the right thing, activists would be harming potential beneficiaries of the products of a company in which PMI was an investor. What account do they take of victims of this cavalier and counterproductive strategy? David Sweanor, a veteran Canadian public health advocate, commented: [6]

“I think the WHO has gone totally off the rails,” said David Sweanor, a lawyer, long-time anti-tobacco advocate and associate professor of law at the University of Ottawa.

“If the World Health Organization is standing in the way of vaccines to treat an epidemic, what does that do to their long-term credibility?”

“Some of my (public health) colleagues have done something really stupid and counterproductive. People they don’t even know are going to suffer and die because of this,” he said.

The underlying policy, says Sweanor, is overdue for review because it discourages companies from diversifying from cigarettes.

Conclusion

In tobacco control activism, no one is required to justify their positions, and there is no accountability for outcomes or unintended consequences. In such circumstances, there is no barrier to tobacco control activists doing or saying things that cause material harm or prolong the epidemic of smoking-related disease. In this case, we can add an insouciant indifference to the victims of a respiratory pandemic and the work of those trying to address it.

A further subject for scrutiny might be the motivation of these activists. Many have spent decades fighting for policies to control diseases caused by smoking and to contain the nefarious influence of tobacco companies. That’s fine; a noble cause. But what if the market is moving to nicotine products that cause minimal or tolerable risks to health? What if vaping and tobacco companies are producing the innovation to end of the epidemic of smoking-related disease? What if nicotine, separated from smoking, becomes a drug with a risk profile more like caffeine or moderate alcohol consumption? Where does that leave today’s tobacco control activists, institutions, and bureaucracies? What will become of their livelihoods, grants, university departments, conferences, travel, media profiles, and even their prestige and identity? Maybe it would be better to conceptualise them as an interest group threatened by progress and judge their actions accordingly.

Shouldn’t readers expect the top academic and medical publications to interrogate these positions more rigorously?

Disclosure

I have no relevant material conflicts of interest, and I am not writing on behalf of or with the agreement or encouragement of any tobacco, nicotine, or pharmaceutical company. I am a long-standing supporter of harm reduction in public health, including for tobacco. I believe that should extend to reducing the harm caused by the commercial activities of the major corporations in this industry.

References

[1] PMI’s Statement of Purpose Excerpt from PMI’s 2022 Annual Meeting of Shareholders and Proxy Statement. [link] [2]. Philip Morris International Inc. 2022 Fourth-Quarter & Full-Year Results, 9 February 2023 [link] and Philip Morris International Reports Progress Toward Accelerating the End of Smoking, Businesswire, 18 May 2021 [link] [3] 123 health groups to PMI: Stop selling cigarettes (press release), October 2017 [link] [4] WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, June 2003 [link] [5] Just Managing Consulting (2020) Contradictions and Conflicts: State ownership of tobacco companies and the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. September 2020. [link] [6] CTV News. How the World Health Organization helped kill a promising made-in-Canada vaccine, 12 February 2023 [link]Clive Bates – The Lancet Respiratory Medicine – 2023-02-10.